Discovering Mr. Holmes

When I was a wee lad, my favorite heroes were the swashbuckling ones. Zorro, the Three Musketeers, Captain Blood, the Count of Monte Cristo. I also like Batman and Superman, but my access to comics in those days was limited, so except for the occasional TV airing of one of the old Batman serials, George Reeves as Superman was my only superhero fix. This was early ’60s, and on almost any Saturday afternoon, when the morning cartoons were done, I could plunk myself down in front of our tiny black and white TV and be relatively sure of finding Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power dashing about at some sort of derring do.

Tyrone Power vs. Basil Rathbone in The Mark of Zorro. One of my all-tome favorite film duels. Little did I know as a child that I’d eventually become even more fascinated by another of Rathbone’s roles—one for which he would become famous, and with which his name would be synonymous for a generation.

Tyrone Power vs. Basil Rathbone in The Mark of Zorro. One of my all-tome favorite film duels. Little did I know as a child that I’d eventually become even more fascinated by another of Rathbone’s roles—one for which he would become famous, and with which his name would be synonymous for a generation.

My father didn’t watch television that much. Oh, he’d watch the evening news, and maybe a bit of Ed Sullivan on Sunday night, but for the most part, he preferred reading for his entertainment. So it surprised me when one Saturday afternoon — I must have been about five or six – I was settling down to watch an Errol Flynn movie, when my father announced he wanted to change the channel, as there was a movie he wanted to see. It’s typical of my relationship with my father that even though he could have arbitrarily insisted, instead, he tried to persuade me that I’d enjoy watching this film with him. The film was The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

“Who’s Sherlock Holmes?” I asked, intrigued, but not really wanting to give up Errol Flynn’s swashbuckling.

“Trust me, you’ll like him,” my Dad said. “He has a cape.”

Apparently, my father had noticed that one commonality between these characters I loved was that many of them wore capes. Grudgingly, I agreed.

As it turned out, there was no cape in evidence until the very end of the movie (and then it wasn’t a proper cape, but a short-caped Inverness coat), but after the first few minutes, it hardly mattered. I was enthralled. And when it comes to Sherlock Holmes, I’ve been that way ever since.

Basil Rathbone, Ida Lupino, and Nigel Bruce. Publicity shot for The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939, 20th Century Fox)

Basil Rathbone, Ida Lupino, and Nigel Bruce. Publicity shot for The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939, 20th Century Fox)

Besides reading the entire Holmes canon many times, as well as many of the pastiches later writers created, I’ve seen every Holmes film and television series I could get my hands on, from Nicholas Roeg’s college age Young Sherlock Holmes to Ian MacKellan’s borderline senile version in Mr. Holmes, from the silent films of Ellie Norwood to the latest Robert Downey films, from Sheldon Reynolds’ 1950s TV series with Ronald Howard, to Grenada TV’s shows with Jeremy Brett, and CBS’ Elementary with Jonny Lee Miller.

When I conceived the idea of writing about Holmes films, it seemed a little daunting to just jump in at the deep end. With the possible exception of Dracula, Holmes has appeared in more films than any other literary character, so the field is a huge one. Even brief write-ups on every film would be a herculean task. Where to even start? With the ones I thought were best? With the most popular? The most canonical?

I decided to start with the canonical films – those that were actually based on Doyle’s original stories. That limited the field considerably. Since there have been a good number of television series over the years which took on the short stories, to limit it even further, I decided to take on only feature length films (this will include television series dramatizations that run to feature length, as well as made for TV movies).

(I’ll also reserve the right to now and then depart from the series to ramble on about other random Sherlock Holmes films, as the whim takes me. As Chuck Wendig might say, shut up, it’s my blog, dammit.)

So I’ll begin this series with a consideration of the films based on The Sign of Four.

“A Singular Case”

Making films based on Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales is a challenge. Most of the Holmes tales are short stories, which would need considerable padding to extend them to feature length. Of the four novels, three have extensive flashbacks revealing the history of the case, in which Holmes plays no part, and the fourth, The Hound of the Baskervilles, has Holmes offstage for a long period. Most canonical films settle on either The Sign of Four, or the Hound of the Baskervilles. Sign has the shortest of the three flashbacks, and Hound contains elements which could appeal to horror film fans as well as mystery buffs.

The Hound of the Baskervilles is the best known, and more often filmed; there are over twenty film versions of Hound, while The Sign of Four boasts less than a dozen (A Study in Scarlet and The Valley of Fear have each been done once, but the former, made in 1933 with portly Reginald Owen as Holmes, has little to do with the book except for the title, and the latter, made in 1916 starring H.A. Saintsbury, is lost). While Hound might appeal to both mystery and horror buff, it nevertheless presents problems of its own. Although unlike the other three novels there is no long flashback, Holmes remains offstage through much of the book — if you’re relying on a famous character to draw your audience, it’s a bit counter intuitive to have that character disappear for large swathes of screen time. And while the tors and marshes of Dartmoor may be very atmospheric, they are not the foggy gaslit streets with which Conan Doyle’s creation is mostly associated. For a feature film which presents the most classic and archetypal version of a Sherlock Holmes tale, The Sign of Four has got to be the pre-eminent choice.

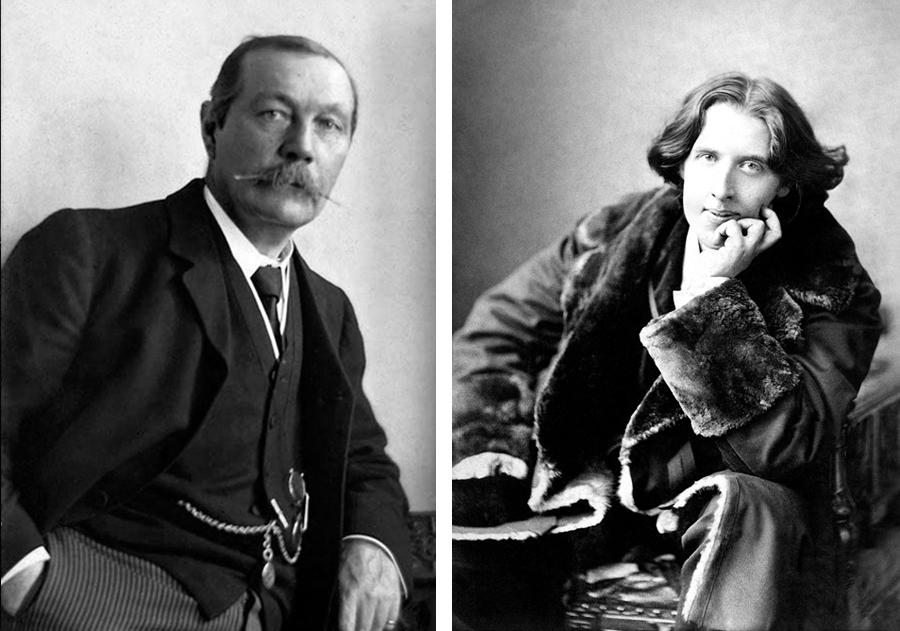

Literary giants met over dinner: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (L), Oscar Wilde (R)

Literary giants met over dinner: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (L), Oscar Wilde (R)

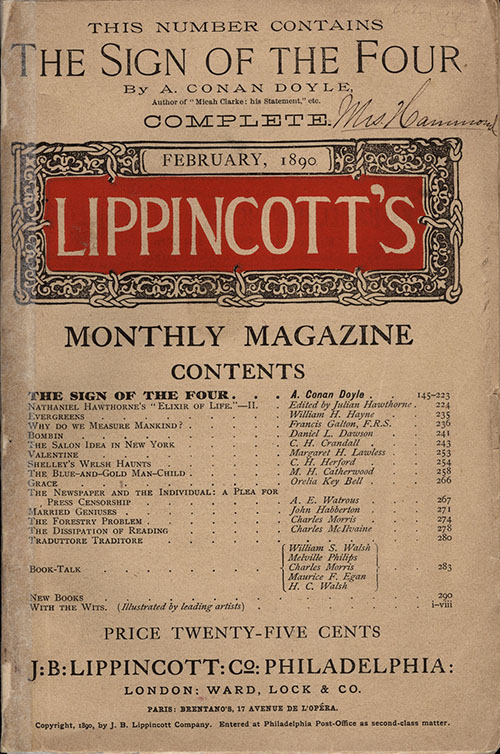

In 1889, Arthur Conan Doyle was at a dinner at the Langham Hotel with Oscar Wilde and Irish MP Thomas Gill, hosted by Joseph Stoddart, the editor of the American Lippencott’s Magazine. Stoddart wanted to start a British edition of Lippincott’s, and proposed to commission works from both Doyle and Wilde. The result was the publication in Lippincott’s Magazine of Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Doyle’s The Sign of Four.

Doyle would later write of that evening at the Langham “It was indeed a golden evening for me.” and of Wilde, “His conversation left an indelible impression upon my mind.” (Doyle, Memories and Adventures, Chapter 8). That impression clearly influenced Doyle’s creation of the character of Thaddeus Sholto in The Sign of Four. Sholto, like Wilde, is an aesthete, describing his sumptuous orientalist apartment as “An oasis of art in the howling desert of South London.” Doyle also describes Sholto in terms that could easily have described Wilde: “Nature had given him a pendulous lip, and a too visible line of yellow and irregular teeth, which he strove feebly to conceal by constantly passing his hand over the lower part of his face.” (Doyle, The Sign of Four, Chapter 4)

Published by Lippincotts as a serial titled The Sign of the Four; or The Problem of the Sholtos, on subsequent publication as a book, the second “the” was dropped, along with the subtitle.

We’ll begin next time by taking a look at two of the earliest film versions of Sign.

Next: The Early Films: Silents and Black and White

"Duncan Eagleson's Viking Snow White retelling, "Snovhit" [has] an authentically ancient feel."

"Duncan Eagleson's Viking Snow White retelling, "Snovhit" [has] an authentically ancient feel."